India’s startup ecosystem is entering a new regulatory era as the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (DPDP Act) begins reshaping how companies collect, use, store, and secure personal data. For early-stage startups, the law marks the country’s first comprehensive framework dedicated exclusively to digital personal data, placing legal accountability directly on businesses that determine how and why user data is processed. Founders building technology products, consumer platforms, SaaS tools, fintech applications, and AI-driven services now face a compliance landscape that is no longer optional or deferable.

The DPDP Act was passed by Parliament in August 2023 to establish a national standard for handling digital personal data. It applies to personal data processed in digital form within India and also extends to processing outside India if it relates to offering goods or services to individuals in India. This extraterritorial scope means even globally incorporated startups serving Indian users fall under its reach. The law introduces a structured system of rights for individuals and obligations for entities that process their data, referred to legally as Data Fiduciaries.

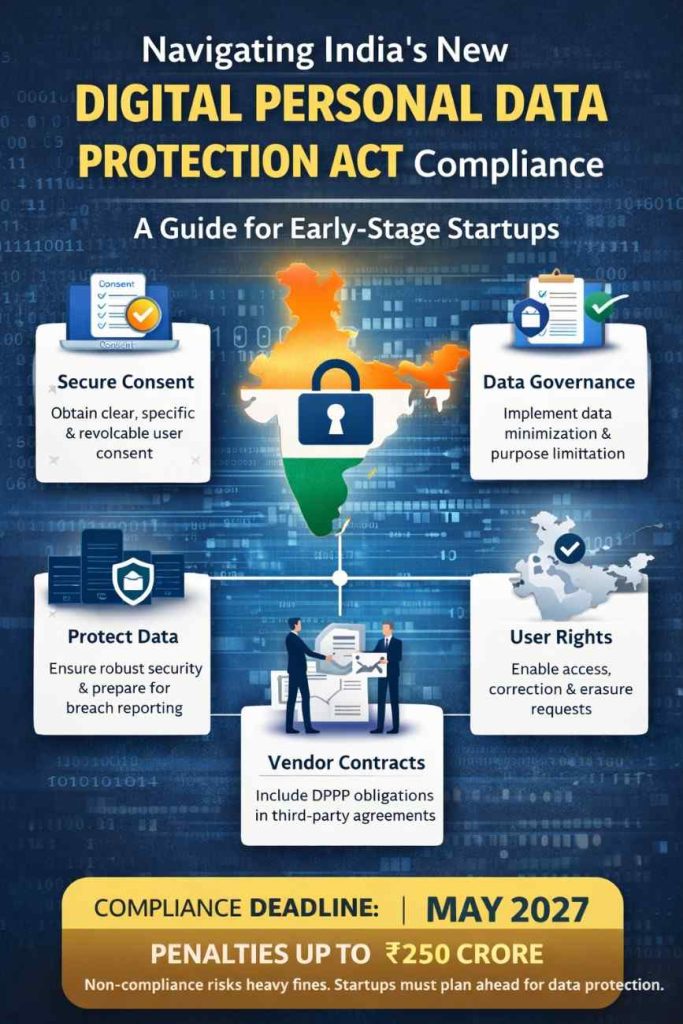

For founders, the most immediate shift is the centrality of user consent. The law requires that consent be free, specific, informed, unconditional, and unambiguous, supported by a clear affirmative action. Pre-ticked boxes, bundled permissions, or vague disclosures do not meet the standard. Users must also be able to withdraw consent as easily as they gave it. This requirement directly affects onboarding flows, sign-up pages, cookie banners, and in-app permissions. Startups that previously relied on broad terms and conditions to justify wide data usage must now redesign their consent architecture to be granular and purpose-driven.

The Act also requires that notice be given before or at the time of data collection. That notice must describe what personal data is being collected and the specific purpose for which it will be used. Legal experts emphasize that the notice should be understandable to an ordinary user and not buried inside dense legal language. For early-stage companies, this creates a practical need to rewrite privacy notices and user disclosures in plain language while keeping them legally complete.

Another operational impact comes from the principle of purpose limitation. Personal data can only be processed for the purpose for which consent was obtained or where the law recognizes a legitimate use. If a startup later wants to use the same dataset for a new feature, analytics model, or marketing campaign that falls outside the original purpose, fresh consent is required. This affects product roadmaps and growth experiments that depend on repurposing user data. Closely related is the expectation of data minimization, meaning companies should only collect data that is necessary for the stated purpose rather than gathering information speculatively.

The DPDP framework grants individuals several enforceable rights. Users have the right to obtain information about their data, request correction or erasure, and seek grievance redressal. Startups must therefore build internal workflows to respond to user requests within reasonable timeframes. Even small teams will need a defined channel, whether through a dashboard or support system, to handle data access and deletion requests. Ignoring or delaying such requests could expose companies to regulatory action once enforcement mechanisms are fully operational.

Children’s data receives heightened protection under the law. Processing personal data of children requires verifiable parental consent, and targeted advertising directed at children is restricted. Any startup offering services likely to be used by minors, including education platforms and gaming apps, must implement age-gating and parental consent mechanisms. This adds a layer of product and compliance design that many early-stage founders had not previously planned for.

Security safeguards are not described in the Act through a fixed technical checklist, but the obligation is clear: organizations must implement reasonable security measures to prevent personal data breaches. In practice, this means access controls, encryption where appropriate, secure development practices, vendor risk assessment, and incident response planning. In the event of a personal data breach, companies are required to notify the designated authorities and affected individuals. That requirement turns cybersecurity from a purely technical concern into a board-level governance issue, even for seed-stage ventures.

The law establishes a Data Protection Board of India to adjudicate non-compliance and impose monetary penalties. The penalty framework is significant, with fines that can reach hundreds of crores of rupees depending on the nature and severity of the violation, including failures to protect data or to meet obligations related to children’s data and breach notification. While regulators have indicated that implementation will be phased and calibrated, the scale of potential penalties has already prompted investors and enterprise customers to ask sharper due-diligence questions about privacy readiness in startups.

Cross-border data transfers are permitted under the Act, but subject to conditions that allow the government to restrict transfers to certain jurisdictions if necessary. This is an important clarification for startups using global cloud infrastructure or overseas processors. Founders must maintain visibility over where their user data is stored and processed and ensure contractual protections with cloud providers and SaaS vendors.

Legal and compliance advisors say one of the most practical first steps for startups is to conduct a data mapping exercise. That involves identifying what personal data is collected, from which sources, where it is stored, who has access to it, and with whom it is shared. Many young companies discover during this process that data flows are more complex than assumed, particularly when multiple third-party tools are embedded into their stack. Without accurate data maps, meaningful compliance is difficult.

Another emerging best practice is appointing a responsible internal contact for data protection matters, even if the law mandates a formal data protection officer only for entities classified as Significant Data Fiduciaries. For early-stage startups, this role is often assigned to a founder, legal lead, or senior engineering manager who coordinates consent design, vendor contracts, security practices, and user rights handling.

Investors are also recalibrating expectations. Venture capital firms and institutional backers increasingly treat data governance as part of operational maturity. Startups that can demonstrate structured consent flows, updated privacy notices, vendor agreements with data protection clauses, and breach response readiness are viewed as lower risk. In sectors such as fintech, healthtech, and enterprise SaaS, customers now routinely request privacy documentation during procurement.

Policy specialists note that the DPDP Act is designed to be technology-neutral and principle-based, allowing flexibility as business models evolve. For founders, this means compliance is not a one-time checklist but an ongoing governance practice that must evolve with the product. Features built on AI models, behavioral analytics, and personalization engines must be evaluated through the lens of purpose limitation and user consent.

For early-stage startups balancing speed and survival, the instinct may be to postpone compliance work. However, industry advisors caution that retrofitting privacy controls after scale is more expensive and disruptive than embedding them early. Consent-aware design, limited data collection, and transparent user communication often simplify architecture rather than complicate it.

India’s digital economy is moving toward a trust-based regulatory model where user data is treated as a protected asset, not a free raw material. The DPDP Act formalizes that shift. For founders, navigating compliance is no longer just a legal necessity but a strategic business function tied to credibility, funding, and long-term growth.

Add startupmagazine.in as preferred source on google – Click Here

Last Updated on Wednesday, February 4, 2026 7:57 pm by Startup Magazine Team